Some people imagine autonomous cars as a kind of utopia where accidents, signs, traffic jams, and parking problems are a thing of the past. But there are also some people who see this situation as a dystopia and believe that a robotic system will run our cities into ruin: we will no longer pay fines, parking tickets, or fuel taxes. Between these two options we find the middle ground of “autopia,” a more sensible and realistic vision of what the incorporation of totally automated vehicles would mean for mobility.

“Autopia” as such does not exist. Well, in fact it does: autopia was the name given to a project led by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) launched in 1996 to create a self-driving car. It is also the name of a ride at Disneyland Paris with vintage cars. The term was recently used by Raúl Rojas, professor at the Free University of Berlin, and Rene Millman, artificial intelligence (AI) and mobility expert. Last January, they both put their names to the article Urban autopia (self-driving vehicles). Mobility and sustainability in the cities of the future for Digital Future Society, an initiative led by the Spanish government and Mobile World Capital Barcelona.

Rojas and Millman “traveled in time” to 2050. They learned all about the autonomous car industry, testing, technological advances, legislative changes, plans for smart cities, and much more. They imagined that more than 6.3 billion people were living in cities

— UN estimates — where mobility is an essential element to ensure citizens lead a healthy life. Driverless taxis and autonomous public transport; much fewer privately owned cars; elderly and disabled people traveling in robotized vehicles; automated vehicle fleets parked in the outskirts where they take up less space and free up areas in cities for public use; sensors on roads, curbs, and sidewalks that allow these vehicles to foresee unexpected and dangerous situations; cars that have been trained to stay in the middle of their lane; digital infrastructures that provide real-time information to each vehicle.

In 2015 in Spain, the General Directorate of Traffic issued an instruction allowing tests with autonomous cars on roads with traffic, but the Law on Third-Party Liability and Insurance does not consider driverless vehicles

How the world moves

Even though we are talking about 2050, some voices believe that we will see the impact of autonomous cars earlier than this. The consultancy firm PwC estimates that autonomous vehicles will account for 40% of all road mileage by 2030. The city of Las Vegas (USA) already has autonomous taxis, where a human still sits in the driver’s seat. An autonomous electric minibus makes simple journeys at the Autonomous University of Madrid or in the National Park of Timanfaya (Lanzarote); a vehicle of the future will travel from Vigo to Oporto in what is considered to be the first cross-border test; Waymo, Google’s autonomous car subsidiary, has tested its robotized driving system on the roads of 25 US cities and is starting to implement autonomous delivery trucks; and the Chinese manufacturer Huawei has announced that it will have an operational autonomous electric vehicle by 2025.

Do all these tests mean that we will soon be seeing driverless cars on our roads? “Autonomous cars as we all understand them — I get in my car and it drives me to work — still have a long way to go. This already exists, and we call it the taxi. On the freeway we will probably soon be able to see a truck with a driver heading up a group of driverless trucks that receive instructions from the leading vehicle. I think this will be more viable in ten years’ time. Or maybe we will even see them being used in courier services within the premises of large companies, but autonomous driving in transportation that carries people is more complicated. It already exists on captive routes that are limited and closed, but I think it’s much more difficult on open routes,” explains Rodrigo Encinar, supervisor of R&D at CESVIMAP, MAPFRE’s Experimentation and Road Safety Center.

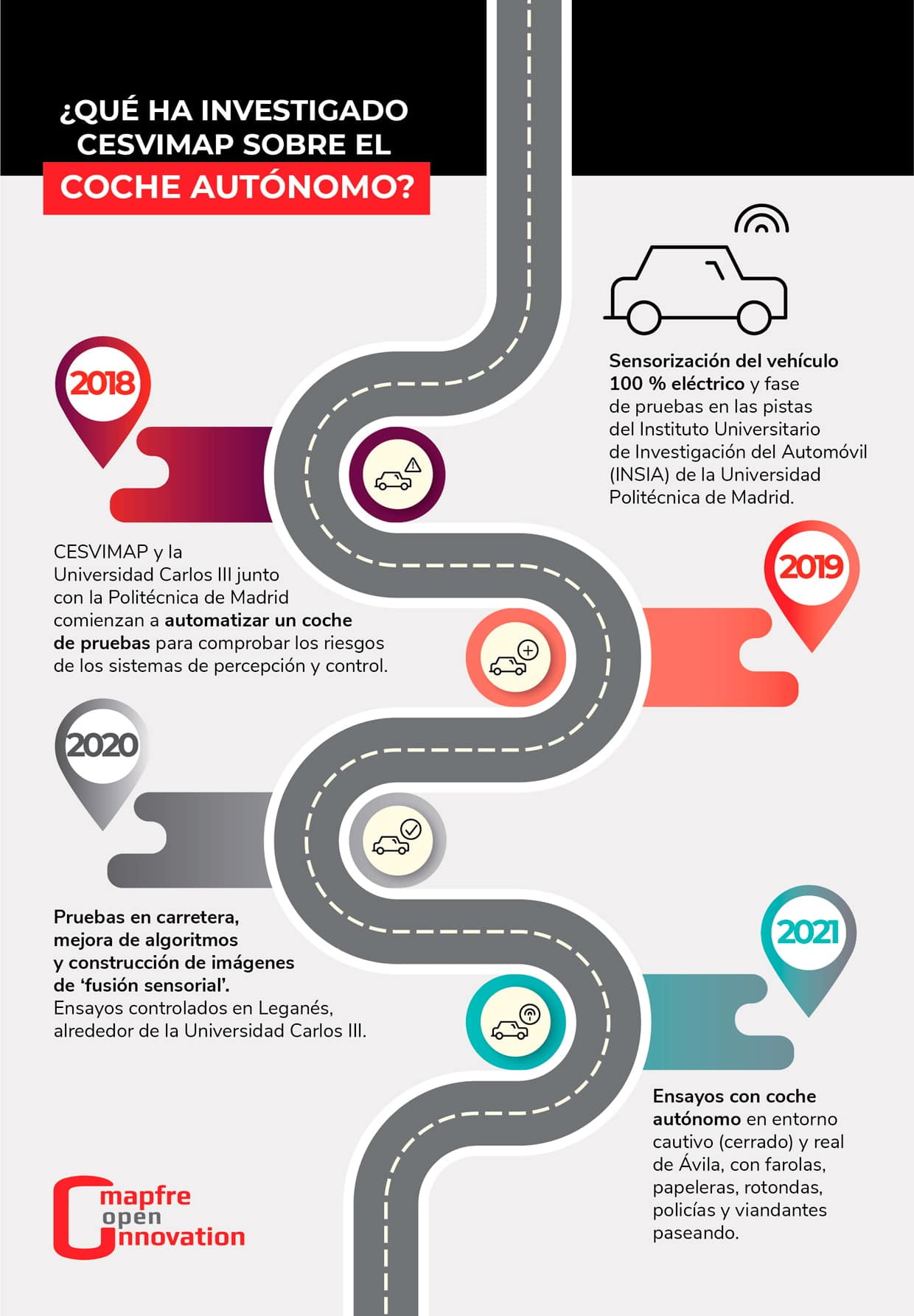

MAPFRE tests the autonomous car

MAPFRE, at its R&D center, has been testing autonomous cars since 2018 in collaboration with University Carlos III and the Technical University of Madrid. The project analyzes the situational awareness and control technologies used in these vehicles. Why? To find out how they behave and establish the risks and possible errors. In June 2021, a 100% self-driving car automated by MAPFRE called ATLAS (Advanced Test Platform for Autonomous System) carried out a conventional urban journey over the course of several days and in real traffic conditions. “We want to see which decisions it makes and observe how the awareness systems detect lines, curbs, streetlights, roundabouts, etc., to see which option it chooses when faced with these problems,” explains Encinar. “We have switched out and tested several sensors and radars and new software systems so we can see the risks posed by each option. For instance, the sensor class, rain or fog can affect GPS positioning,” indicates the R&D specialist.

Many of these vehicles have a built-in LiDAR radar and send out pulses of light, which bounce off obstacles and build a point cloud. An AI algorithm evaluates this map and interprets the surroundings. “For example, it is very difficult to distinguish between a plastic garbage can and a truck using LiDAR technology because they both generate the same point cloud, but if we were using radar, they waves would pass through the plastic object and wouldn’t bounce back. A camera with computer vision would be able to tell a car apart from another object, but it couldn’t calculate distance correctly,” explains Encinar.

One possible solution is sensory fusion, grouping different layers of sensors together in an image and processing them in an attempt to gain a perfect understanding of the surroundings. “We are currently analyzing sensory fusion to establish the implications of awareness errors on road safety and whether these are related to the design or algorithms,” ensures the expert from CESVIMAP.

With this initiative, CESVIMAP, University Carlos III of Madrid, and Insia are pioneers in the research of autonomous driving technologies: ultrasound and infrared sensors, satellite positioning and navigation tools, camera systems, and radars. Their conclusions will be essential to position the Spanish insurance company in the autonomous car ecosystem.

- Level 0. All driving tasks are carried out by a human, and there may be an automated assistant that can detect other vehicles in the blind spot, but at level 0 there are actually no automated functions i.e. the cars we have had for years (or used to have years ago).

- Level 1. These vehicles use an ADAS (Advanced Driver Assistance System), which will be obligatory from 2022, to control lateral and longitudinal movements, but not both at the same time. This could include lane departure warning or cruise control systems. The car is completely dependent on human action.

- Level 2. Electronic assistants manage the two movements, but only the driver is in charge of the vehicle. In practice, these assistants can keep the car in the middle of the lane and set the speed simultaneously (that is the key).

- Level 3. The driver does not need to supervise driving, but they must be alert and intervene when prompted by the system in the event of a risky situation.

Legally speaking, this is the most obscure level because it is not known who would be liable if an accident occurs. - Level 4. The automation system is capable of acting autonomously in the face of unforeseen circumstances and can drive the car for a sustained period of time, but only in certain environments.

- Level 5. The automated driving systems do not require a human driver and have no geographical or climate-related limitations.

Google has tested its robotized driving system on the roads of 25 US cities and is starting to implement autonomous delivery trucks

Huawei has announced that it will have an operational autonomous electric vehicle by 2025

“This is a legal challenge, not a technological one”

Francisco Javier Falcone, professor in the Communications and Signal Theory Area at the Public University of Navarre, admits that it is uncertain when we will start seeing autonomous cars on our roads, but ensures that the problem does not lie in the technological challenge because “technology will evolve. In terms of communications, the establishment of a pure 5G network is expected to eliminate the delay of milliseconds that could provide an extra level of safety in decision-making.”

“It is a legal challenge, argues Falcone”, the legislative framework that underpins the use of autonomous cars is less advanced than our level of knowledge. Science continues to move forward, and I am certain that not too far in the future we will see autonomous cars on our roads, but the law needs to adapt to this new situation.”

In the United Kingdom, the government has created a body to allow tests on freeways and in cities; in France, a legal framework was approved in 2019 with the same aim and the (not very realistic) goal of implementing “highly automated” vehicles by 2022; and Japan gave the go-ahead to a regulation regarding the use of partially automated cars, which must be equipped with systems that record travel data so they can be analyzed in the event of an accident.

Germany wants to be the “first country in the world to bring autonomous vehicles from its research laboratories onto the road,” affirmed Andreas Scheuer, Minister for Transport. To reach this goal, Germany intends to approve specific legislation for level-4 vehicles focused on public transport, business routes, logistic routes, and transportation of elderly people and medical patients. “And despite this, brands like BMW and Mercedes have announced their withdrawal from autonomous driving to focus on level 2,” mentions Rodrigo Encinar from CESVIMAP.

In 2015 in Spain, the General Directorate of Traffic issued an instruction allowing tests with autonomous cars on roads with traffic, but the Law on Third-Party Liability and Insurance is outdated and does not provide for driverless vehicles. In addition, the requirements to receive this level-3 authorization are exhaustive, and the Ministry for Industry has no technical services that are capable of fully validating fulfillment of these conditions. Consequently, there are no certified level-3 vehicles in Spain.

In June 2021, a 100% self-driving car automated by MAPFRE called ATLAS (Advanced Test Platform for Autonomous System) carried out a conventional urban journey over the course of several days and in real traffic conditions

The establishment of a pure 5G network is expected to eliminate the delay of milliseconds that could provide an extra level of safety in decision-making

the legislative framework that underpins the use of autonomous cars is less advanced than our level of knowledge. Science continues to move forward and not too far in the future we will see autonomous cars on our roads, but the law needs to adapt to this new situation

Who should be insured?

The other big debate is related to liability in the event of an accident. We are currently at level 2, using ADAS, technology that prevents risks and where the driver is ultimately in charge of the vehicle. MAPFRE is testing level 3 vehicles, where responsibility is shared: the vehicle can make certain decisions autonomously but asks the driver if it is not sure what to do and returns control. “We have to define who is liable in the event of an incident so we know who should be insured: The vehicle manufacturer? The sensor manufacturer? The software developer? Will there be more than one insurance policy?” Rodrigo Encinar wonders.

The ethical issues are more concerning. “This problem comes into play when the autonomous car’s reasoner (artificial intelligence) has to make a decision that could put the lives of the vehicle occupants or people outside of the vehicle in danger. How does it make this decision and, in the event of an accident, who has subsidiary liability? Should the computer or the algorithm be insured? This is the great legal issue, and it probably poses a bigger challenge than technology,” states this professor from the Public University of Navarre.

“In theory, the AI should weigh up all variables, including the human cost, and take the option that causes the least damage to people. For example, if I am either going to run over five people or have an accident, the reasoner should avoid these people,” he comments.

In addition to testing sensor systems and the possible risks, through CESVIMAP, MAPFRE also wants to find out what if feels like to be a driver in an autonomous car. “In my case, the first time I sat in the passenger seat I felt a bit unsafe and stressed,” confesses Encinar, “and it made me realize the value of people. Human beings are one-of-a-kind because of what they can do, when you dodge an obstacle, when you see a child on the sidewalk that is going to cross the road … and cars aren’t just something that gets us from point A to point B; they give us a sense of freedom, and I don’t think everyone would be willing to give up driving. However, for people that can no longer drive because they have reached a certain age, autonomous cars will allow them to lead a similar life to when they had a car.”