In 1989, the second installment of the legendary movie trilogy Back to the Future depicted a home in which the doors were opened with buttons, the windows were replaced with projections of landscapes, the food was cooked in a “hydrator” and telephone calls were answered from spectacles or the television. With plenty of nuances, the scenarios we imagined then, through the adventures of Marty McFly and Doc Emmett, are increasingly similar to what we see today in our 21st century homes, structures that have progressively introduced automation to how they function… and there is no going back. A whole universe of opportunities is opening up, but there are also risks to which the insurance industry must respond.

TEXT Javier Ortega | PHOTOS Thinkstock

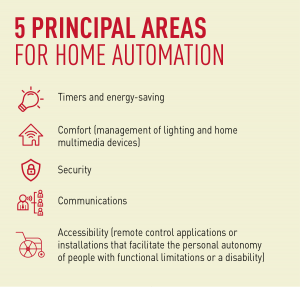

The concept of domotics, a portmanteau of domus (house in Latin) and automatic, from the Greek automatos (selfacting), was coined in the early 1970s when, as a pilot project, the first smart devices were integrated into buildings. Almost 50 years later, digital homes are a reality and there is an evergrowing number of connected dwellings in which it is feasible to mechanize and optimize tasks that have traditionally depended on our direct intervention.

The possibilities seem almost endless and, among the options offered by technology, the most highly valued are those related to the Internet of Things (IoT) and management systems enabling communication between all the electronic devices in the home. In practice, this translates into a new use over the network of networks of objects such as cameras or sensors, which were previously only connected via closed circuits. Although, at the moment, the IoT proves more successful in sectors such as health or the control of urban infrastructure, the explosion of the use of the “smart” label in homes is coming on strong thanks to an industry that has been profiting from it for a long time – smartphones.

NEARLY 50 YEARS LATER, DIGITAL HOMES ARE A REALITY

Smart, ecological and efficient

from our cell phone we can now: control cameras to monitor our babies or the interior of our home; check the temperature of the oven in the kitchen; turn lights, televisions or the air conditioning on and off; or verify whether the plants need water or fertilizer, and whether the humidity, temperature and light are just right for them. Refrigerators that alert you when you are running out of food, robots that set about cleaning the home whenever it is empty, air purifiers which are activated whenever they detect harmful particles in the atmosphere… Even though we still use them to make calls, cell phones are well on the way to becoming universal remote control units, and the catalog of devices that can be controlled from them is steadily increasing.

In China, the country which produces most of the world’s electrical appliances, for some time now the major brands have opted for products and applications that meet the three criteria of smart, ecological and efficient. The next step is to increase the interconnections between the devices themselves. We are talking about a scenario that some may find unsettling, in which, for example, the fridge sends a message to its owner’s cell phone with the food items they should buy in order to abide by a diet stipulated by some gadget which controls their physical condition by monitoring cholesterol levels. Total interconnectivity, although tempting, will not be so easy to achieve, as most of the manufacturers must reach agreements, share information, and negotiate universal standards. In any case, this process will be slightly slower, but it will happen.

More opportunities… and more risks

According to a study by the U.S. consultancy Gartner, over 20 billion devices throughout the world will be interconnected by 2020. What would happen if one of these systems were cracked, thus enabling access for illicit purposes?

Hackers first set their sights on personal computers; later, viruses hit cell phones; and, for some time now, there has been a notable increase in the number of attacks on vehicle control systems. Smart homes are also in their sights and there is already clear evidence of this. For example, in Israel, a group of so-called White Hat hackers demonstrated the vulnerability of latest-generation bulbs by attacking the lighting system of public buildings and private dwellings. It was as simple as passing by in a car (it could also be done using a drone) within 70 meters of one of the bulbs that they were targeting. That was sufficient to infect the first device, with the “infection” then spreading to the rest, taking control of the lighting installation and flashing the lights on and off at will.

Last year, the Spanish National Cybersecurity Institute registered 115,000 cyberattacks on companies and individuals, up 130 percent on the 2015 figure of 50,000. Any device connected to the internet can be a victim, for example, of ransomware, such as the malware used in the global cyberattack in May and which, in June, once again affected companies all over the world. In private homes, there have already been cases of smart TVs infected with this kind of virus.

The role of insurance

Of course, the likelihood of attacks increases with the progressive implementation of technology in ever more areas of our lives, but that should not paralyze us. It is just a question of being more attentive and protecting ourselves better with the options we have at our disposal. And, in this area, the insurance industry has a lot to say. Insurance policies are also developing to cope with the IoT and big data. MAPFRE, for example, as part of its home insurance policy, has for some time now included IT support for laptops, smartphones and tablets, and also offers the possibility of installing antivirus systems, making backup copies of a customer’s files, or restoring data and contents in the event of some problem.

This is the direction in which we are going to keep pushing, furthering the design of new services tailored to the needs of our customers. For Antonio Huertas, MAPFRE’s Chairman and CEO, the new technologies are triggering a true revolution “which may prove to be transformational for the insurance industry within a period of five to ten years.” Logically, this transformation, as is always the case, entails risks and opportunities: “the capacity of existing insurers in the marketplace to discover how to minimize the former and maximize the latter will determine whether or not they survive this revolution and do so successfully. Some risks disappear, others arise, and yet others are transformed. But people will never cease seeking to protect themselves from the unexpected.”